Bang or Whimper?

Bang or Whimper?

Interview in Brisbane zine Don’t Mind Us

Don’t mind us: Inkahoots has hung posters in its street front window as a means of engaging with the local community on a range of social justice and environmental issues. Recently you were ordered to remove a poster from your shop front. Can you describe the poster and what you were trying to communicate with it?

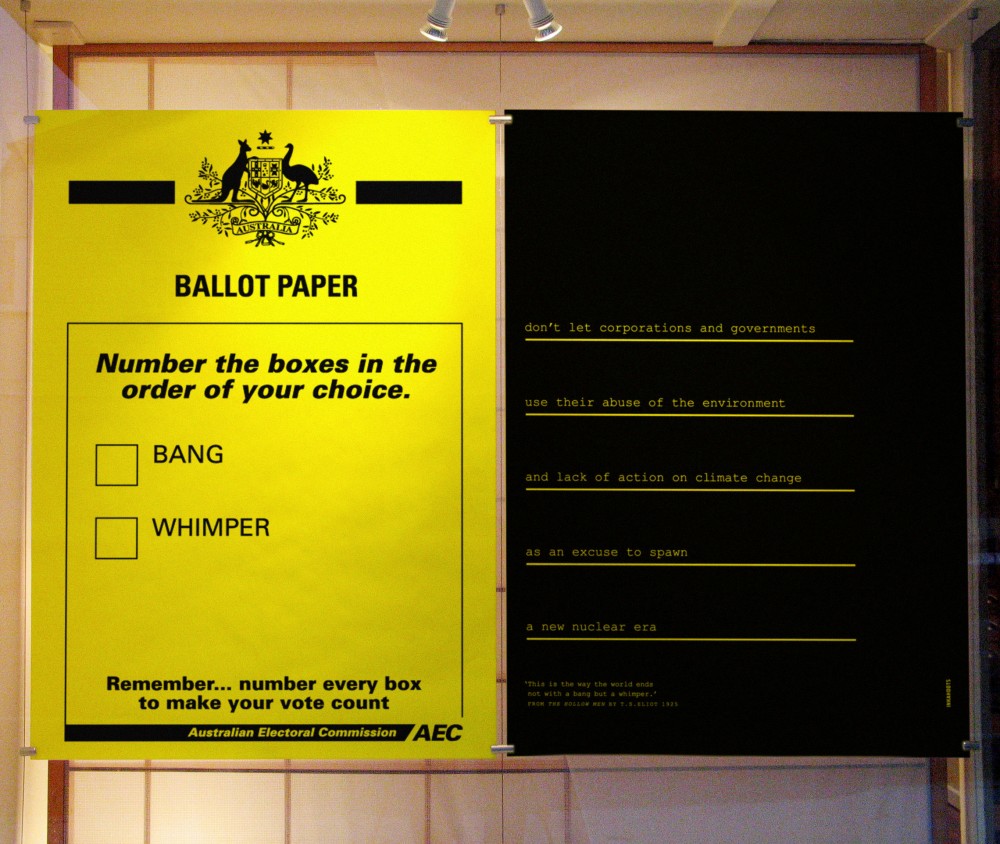

Inkahoots: The posters were part of a campaign responding to the resurgent nuclear debate in Australia. We’re hearing politicians like Howard and his corporate allies claim that in order to address climate change we should adopt nuclear power as an alternative energy source. So after years of denial, policy inaction and environmental vandalism, suddenly they’re all so committed to sustainability? Or are they just smelling serious profits? The poster references the TS Eliot poem The Hollow Men: “This is the way the world ends/ Not with a bang but a whimper” and uses a parody of a federal ballot paper to present ‘Bang’ or ‘Whimper’ as the choice for Australia’s future. Of course the end of the world via environmental degradation or nuclear folly is not much of a choice. So what about a genuine alternative?

What were the events that lead to its removal?

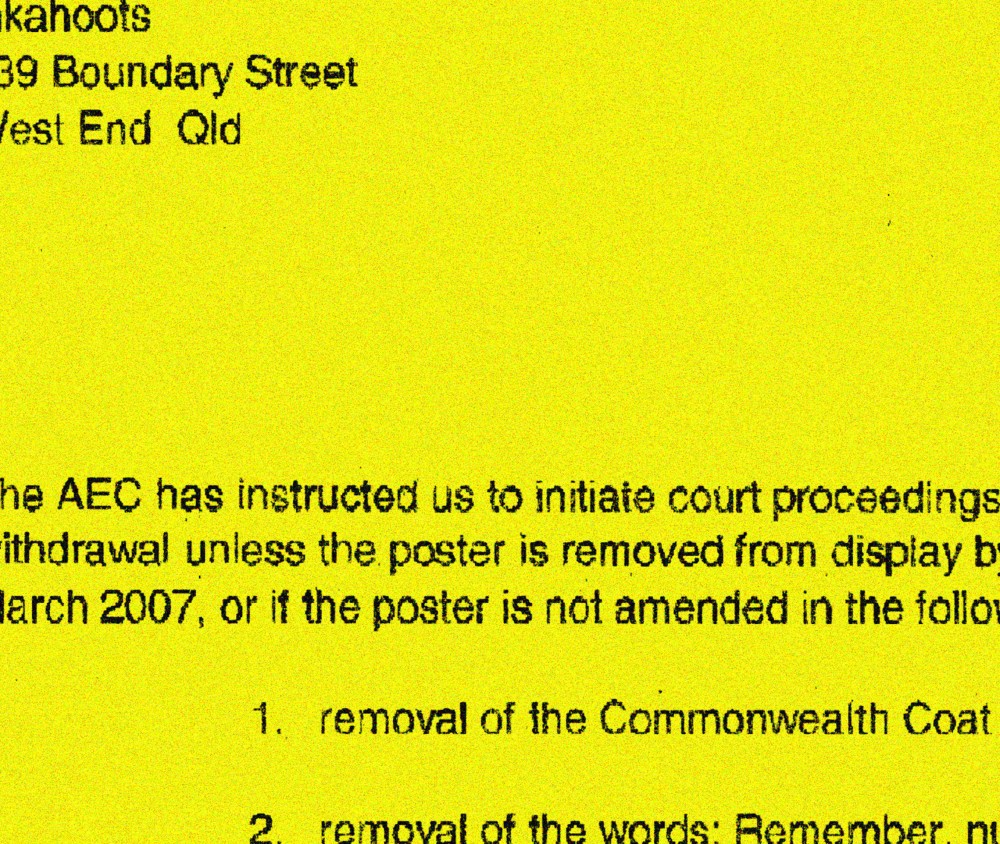

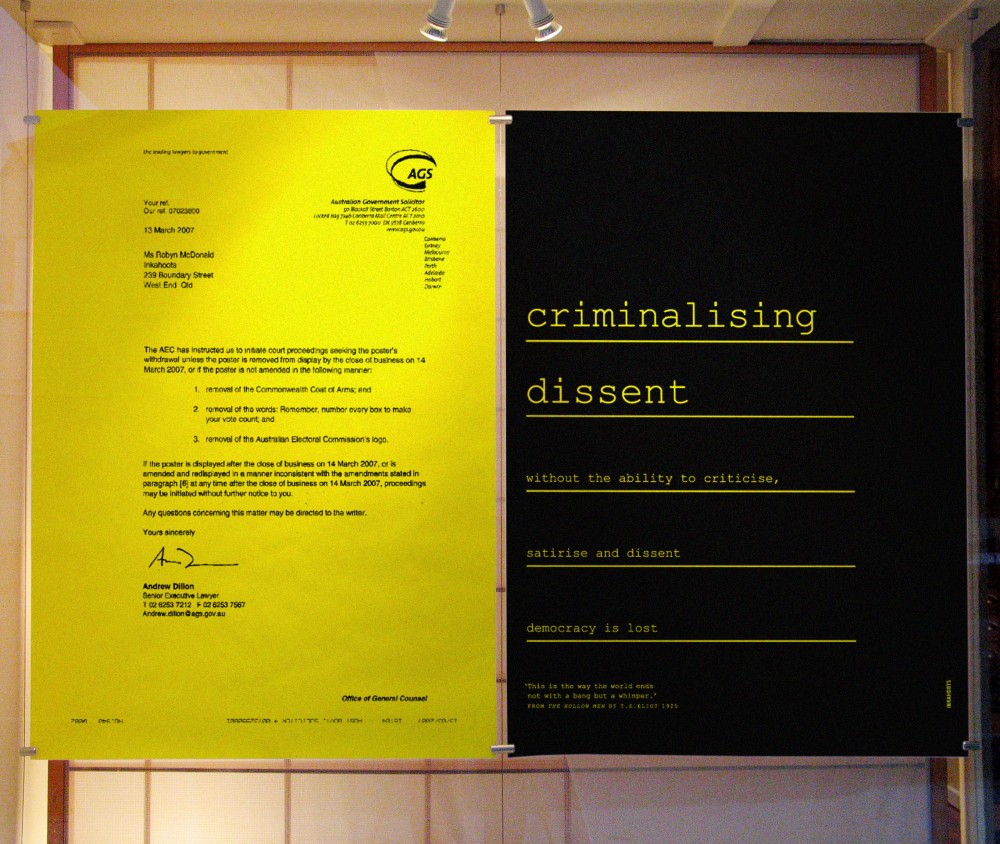

We received a fax in the morning of the 13th of March from the Australian Government Solicitors in Canberra stating that if we didn’t take the posters down by close of business we would be prosecuted. We were hand delivered the same letter again twice during the day. By this stage we figured we’d better get legal advice! The advice was that there was no time to legally challenge the notice, and that if we didn’t comply we should prepare to be visited by police who would have warrants for our arrest and the power to confiscate equipment and files. The Barrister also warned that we should expect that we were being monitored. So we reluctantly removed the posters and put in their place the threatening letter with an accompanying statement about criminalising dissent.

You’d used a trademark of the Australian Electoral Commission. As graphic designers shouldn’t you have known better? Was that what this was all about?

We used the Australian Electoral Commission logo and the Australian Commonwealth crest, as well as wording lifted from an official ballot. When a comedian impersonates a politician most people understand what’s going on... and that they’re not actually the politician. In a delightful conversation with their solicitors, the government argued the average person would think our posters were official documents. Well that’s just disingenuous. Context is everything. And a two-meter high ballot paper presenting the candidates ‘Bang’ and ‘Whimper’, accompanied by a statement explicitly criticizing the government, couldn’t be anything other than satire. In the end what’s more important – perceived intellectual property rights or a citizen’s right to critique power? Artists need to be able to mimic authority in order to parody it. We’d argue that without this ability to criticise, democracy is lost.

You’ve responded by enlarging the letter from the solicitor-general to poster size and hanging it in your shop front. A somewhat audacious move don’t you think? What has been the response to this?

None. As far as we know there’s no legal problem with it.

Do you see this as an isolated incident or do you see it as reflective of the state of free speech and democracy in Australia? Do you often come across political censorship in your work? How does it manifest itself?

I’d guess the political restriction of information in Australia mostly isn’t overt expurgation, but various forms of self-censorship. In a boundless commercial-friendly atmosphere of corporate compliance, with a docile and obedient media, and emasculated public institutions, who needs to be banning shit? But we’d better gag those posters in a West End window just in case.

We’ve pretty much had censorship from every level of government now. In the past it has been works that have been denied exhibition for various breaches of ‘public decency’.

Clive Hamilton, co-editor of Silencing Dissent, says that what we need to defend the democratic process is courageous individuals and courageous organizations who are going to say “I’m not gonna take it anymore”. What I see here is a situation where you’ve taken a stand and been given a choice, you either remove the poster from your window or risk losing the very equipment that your livelihood depends upon. How do you think we can address this culture of silencing, or criminalising, dissent?

Yes, we need those individuals. And those individuals need the right kind of climate often to succeed and not be buried. And this climate in turn depends on our priorities as a community. One of our solicitors very frankly suggested in order to beat this kind of censorship you need to either be a wealthy organisation with resources to burn, or an asset-free activist with nothing to loose. But of course it’s not just the pressure of financial punishment that cows protest, but for many (like journalists and academics for example) it’s also the stigma of personal vilification and professional denigration, and fear for the welfare of their organisations.

How would you describe the health of social and political activism in Brisbane?

There have always been organisations and individuals in Brisbane who are just staggering to us. People who sacrifice and fight for social justice, while the rest of us are making excuses, or making money, or making misery. It’s incredible because they stand against the most successfully seductive force to ever cripple social engagement – more efficient than violence or intimidation – this is the idea that we’re not responsible for each other, but merely for our own, or our families’, material comfort and entertainment. Peace activists like Ciaron O’Reilly who has done time in a US jail for disabling war planes. Our Friend Joe Hurley who has a tireless commitment to the homeless. Friends who have exhausted themselves and compromised their health fighting for the rights of refugees. The resilience and tenacity of the Aboriginal community. You take these people out of Brisbane and you could be forgiven for sometimes thinking the city is just a real estate catalogue.

In your book ‘Public – Private’ you describe a renaissance of sorts following the end of the Bjelke-Petersen era in Queensland, including the ‘birth’ of Inkahoots. Do you think we’ll see a similar resurgence of creativity and activism if Labor brings an end to the Howard era at the next Federal election?

There will be many positive things to come out of Howard’s eventual demise, but we’re not so sure a Labor government will be one of them.

What gives you cause for optimism?

People’s disgusted reaction to this whole censorship episode. We’re optimistic about people’s response to creative repression. And people’s capacity for criticism and rebellion.