Black, Red & Gold

Black, Red & Gold:

A studio conversation about colonisation and visual resistance.

A shorter version of this essay appeared in Threaded magazine. This version is published on Design Observer in memory of Gordon Bennett, one of Australia's great contemporary artists, who died on June 3, 2014.

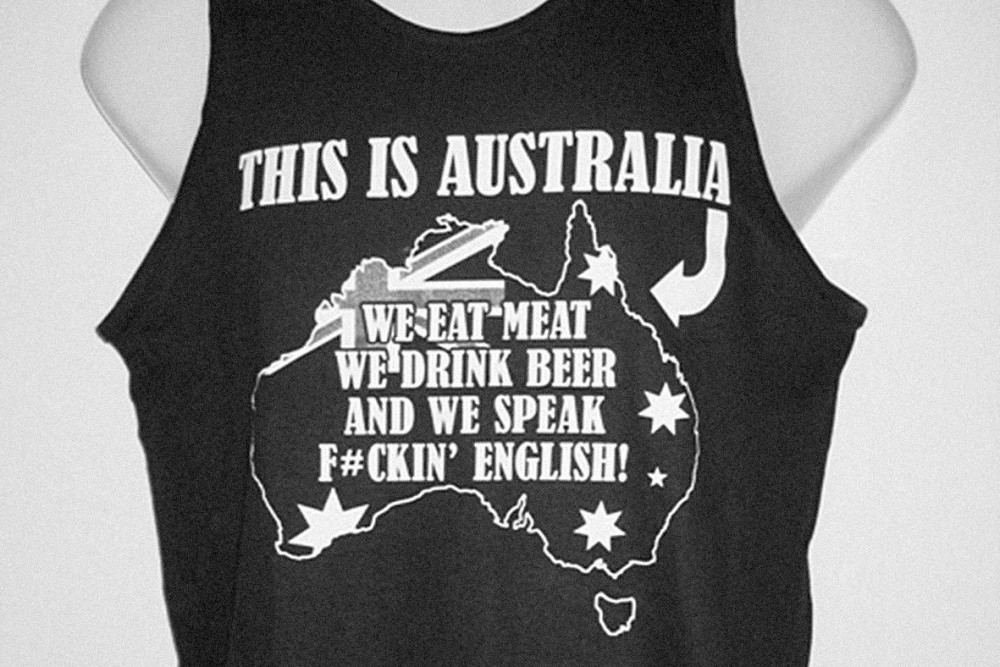

One of three t-shirts comprising a 'Hardcore Aussie Pride' pack. Sold online in 2009 and in a Darwin shop prior to Australia Day 2009.

One of three t-shirts comprising a 'Hardcore Aussie Pride' pack. Sold online in 2009 and in a Darwin shop prior to Australia Day 2009.

Jason Grant: I was at the local markets this morning and out of the crowd came a bloke wearing a blue t-shirt printed with the Australian flag and the text: ‘This is Australia. We eat meat. We drink beer. And we speak f#ckin’ English’. I’ve never had much luck arguing with racists but always figure racism needs to be confronted wherever you find it: What’s with the racist t-shirt mate? / It’s not racist. / Yes it is / No it’s not. / Well some of us don’t speak ‘fucking English’. / So? / So before the invasion Australians spoke hundreds of languages, and none of them were English, and you know there’s a lot of diversity here that needs to be celebrated, not insulted. / So? / So what’s with the racist t-shirt? / It’s not racist – it’s Australian.

And he walked off.

Aboriginal flag at a street march. Photo by Rachel Cobcroft.

Aboriginal flag at a street march. Photo by Rachel Cobcroft.

Ben Mangan: Black voices have always been suppressed by their white colonisers. Let’s start by acknowledging that white-folk talking for and about Aboriginal culture is problematic because that’s been the dynamic since invasion. But instead of marginalisation this discussion is an attempt at understanding, however clumsy, and it comes with deep respect and admiration. It’s also an attempt at mining the studio’s collective knowledge, however limited.

Angela Bliss: The European colonisation of Australia always gets romanticised by white Australians with heroic expressions of denial such as ‘discovery’, ‘settlement’ and ‘explorers’, whitewashing (pun intended) the brutal realities of the invasion.

BM: How does that Kev Carmody song go? “1n 1788 down Sydney Cove the first boat people land / said 'sorry boys, our gain's your loss – we're going to steal your land.”

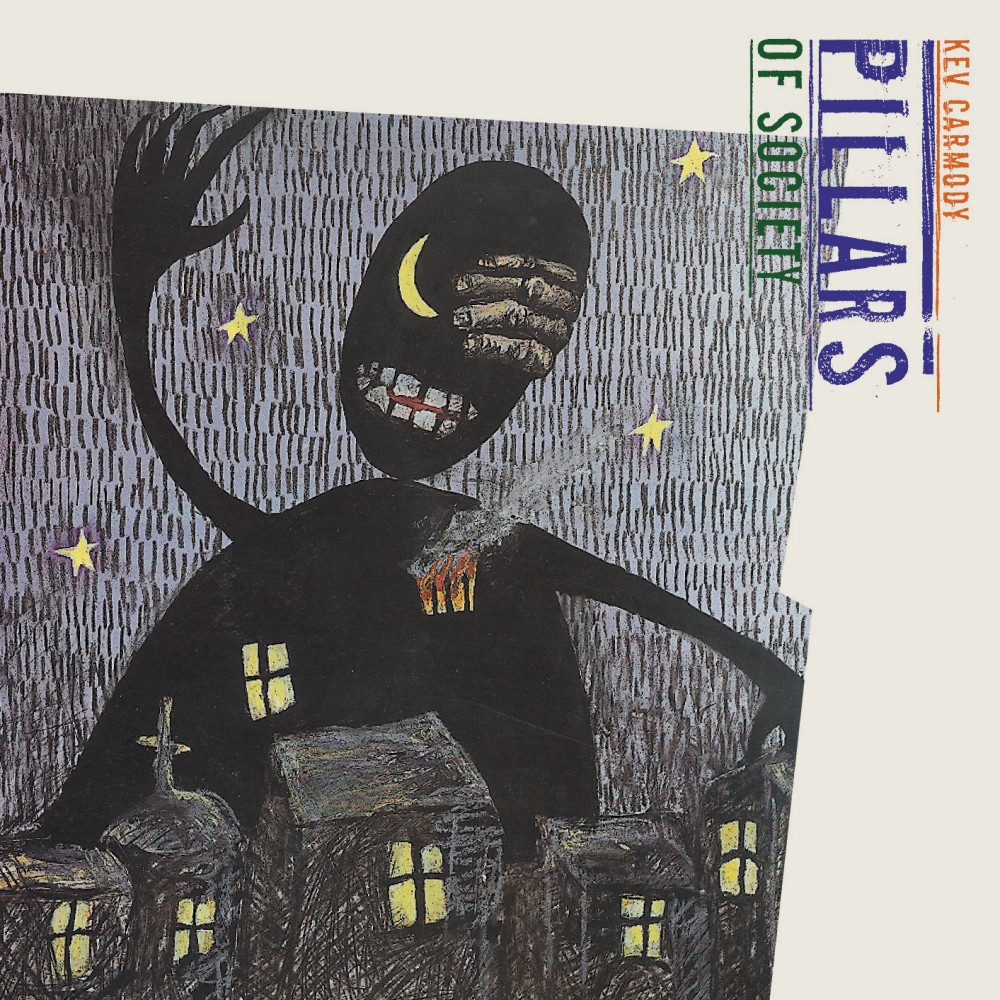

Inkahoots, Pillars of Society by Kev Carmody, painting by Paul Hoyne, CD cover, 1999

Inkahoots, Pillars of Society by Kev Carmody, painting by Paul Hoyne, CD cover, 1999

JG: It’s amazing that it’s only in the last few decades that Aboriginal history has been introduced into school history classes, challenging racist mythologies and confronting Australians with an alternative colonial narrative. I don’t remember learning anything much about ‘natives’ but rather hearing plenty about glorified white explorers. Even as a kid I remember wondering what was so great about Burke and Wills for example, a couple of arrogant adventurers leading their party to starve to death in the middle of Australia. Now the historical fact of genocide is gaining academic and popular acceptance, along with a history of tenacious adaptation and resistance by Aboriginal people.

Eugene Montagu Scott, Natives discovering the body of William John Wills, the explorer, at Coopers Creek, June 1861. Courtesy State Library of Victoria

Eugene Montagu Scott, Natives discovering the body of William John Wills, the explorer, at Coopers Creek, June 1861. Courtesy State Library of Victoria

AB: And we didn’t learn in school that Burke and Wills probably starved because of Beriberi, a thiamin deficiency. That they were being well fed by the local Yandruwandha people until Burke did what white men did then to honour the colonial ethos — he shot at them. That they fled, and within a month the brave explorers were dead, probably because they weren’t properly preparing the seed cakes given by the Yandruwandha. That they were eating but also starving because they weren’t grinding the ngardu sporocarps into a paste to neutralise the thiaminase that depletes the body of thiamine. And we weren’t taught that Burke and Wills were ‘discovering’ country that had been well and truly occupied for thousands of years.

Bretton Bartleet: This is at the heart of historical tensions between white and black Australia — this denial of Aboriginal existence and a culture that goes back 50,000 to 70,000 years, the longest living culture on the planet. British claims to sovereignty over Australia were founded on the doctrine of Terra Nullius, the notion that the whole country was legally unoccupied. And this ‘legal fiction’ wasn’t even overturned until the High Court’s 1992 Mabo decision.

BM: This denial of ‘native title’, this stubborn injustice, has motivated some of Australia’s most important political struggles focused on social justice and land rights, which has in turn inspired a rich legacy of visual defiance.

Nicholas Chevalier Buffalo Range from the West1862. The University of Melbourne Art Collection. Gift of Dr Samuel Arthur Ewing 1938.

Nicholas Chevalier Buffalo Range from the West1862. The University of Melbourne Art Collection. Gift of Dr Samuel Arthur Ewing 1938.

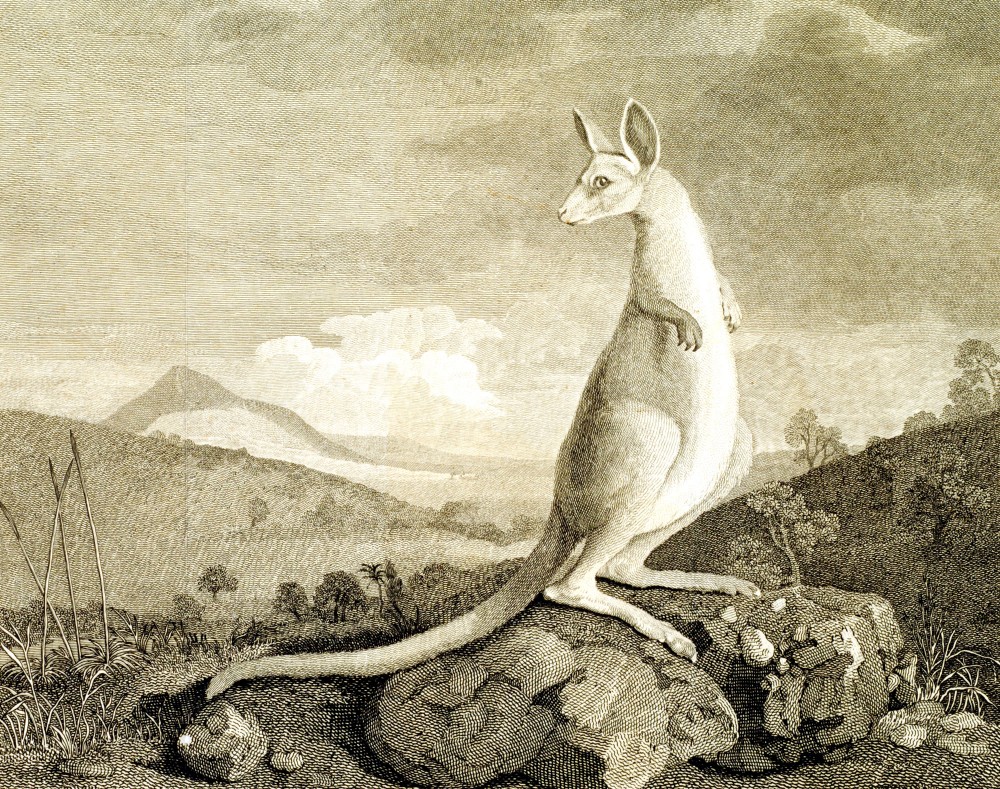

England's first view of a kangaroo, an engraving published in the official account of Cook’s voyage after a painting by George Stubbs, A Portrait of the Kongouro (Kangaroo) from New Holland 1772

England's first view of a kangaroo, an engraving published in the official account of Cook’s voyage after a painting by George Stubbs, A Portrait of the Kongouro (Kangaroo) from New Holland 1772

AB: Land that was the basis of intimate indigenous co-existence, custodianship and spiritual custom was to the British brutishly harsh and difficult terrain. The initial visual responses to these alien landscapes by the colonisers were both symbolic and symptomatic of colonisation itself. Have you seen the paintings of Sydney scrubland by early artists? They were rendered as lush rolling English hills or Swiss Alps, and native fauna, like kangaroos and platypus, were transformed into caricatures of familiar English animals. Imposing European cultural sensibilities on an exotic setting tamed the incomprehensible country and asserted imperial rights: the realities of the Australian landscape were denied along with the traditional owners of the land.

Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri’s, Warlugulong 1977 is one of Australia's most expensive paintings. It was purchased by the National Gallery of Australia in 2007 for A$2.4 million.

Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri’s, Warlugulong 1977 is one of Australia's most expensive paintings. It was purchased by the National Gallery of Australia in 2007 for A$2.4 million.

Emily Kame Kngwarreye painting Earth's Creation, 1996. Photo by Gemma Page.

Emily Kame Kngwarreye painting Earth's Creation, 1996. Photo by Gemma Page.

JG: Yet for many Aboriginal people the land is linked to a complex visual language of tribal mythology. In 1971, the Papunya desert settlement was the first community to translate the ancient ephemeral patterns of circles and dots into art objects embodying ‘dreaming’ stories and sites. The success of Central and Western Desert artists such as Clifford Possum, Emily Kngwarrye and Minnie Pwerle has been phenomenal. The dot paintings that have become Australia’s pride in the international contemporary art market have been used paradoxically to resist infringement by white culture through the coded concealment of sacred cultural knowledge, and as revelatory documents to support land claims and cultural sovereignty. Simultaneously, hasn’t the commercial success of traditional Aboriginal art served to mask constant injustice and disadvantage?

Fiona Foley, HHH #1 2004. Courtesy of Andrew Baker Art Dealer, Brisbane and Niagara Galleries, Melbourne

Fiona Foley, HHH #1 2004. Courtesy of Andrew Baker Art Dealer, Brisbane and Niagara Galleries, Melbourne

AB: Many contemporary urban Aboriginal artists challenge the dominant idea of ‘authentic’ Aboriginal art as a confinement of their practice to ‘traditional’ pre-colonial culture. Artists like Gordon Bennett, Judy Watson, Sally Morgan, Fiona Foley and Tracey Moffatt reject as racist the distinctly imposed categories of ‘Aboriginal’ and ‘contemporary’ art.

Gordon Bennett, Death of the Ahistorical Subject 1993. Courtesy the artist and National Gallery of Australia.

Gordon Bennett, Death of the Ahistorical Subject 1993. Courtesy the artist and National Gallery of Australia.

BB: And Richard Bell highlights neo-colonialist practices in the art market itself. In 2003 he won a big national prize for a painting with the text “Aboriginal Art/It’s A White Thing”, about the inequities of an art market in which Aboriginal artists make work for gallery owners who are mostly white. These gallerists then interpret and ‘colonise’ the works for a broader audience — another mitigation of the Aboriginal voice.

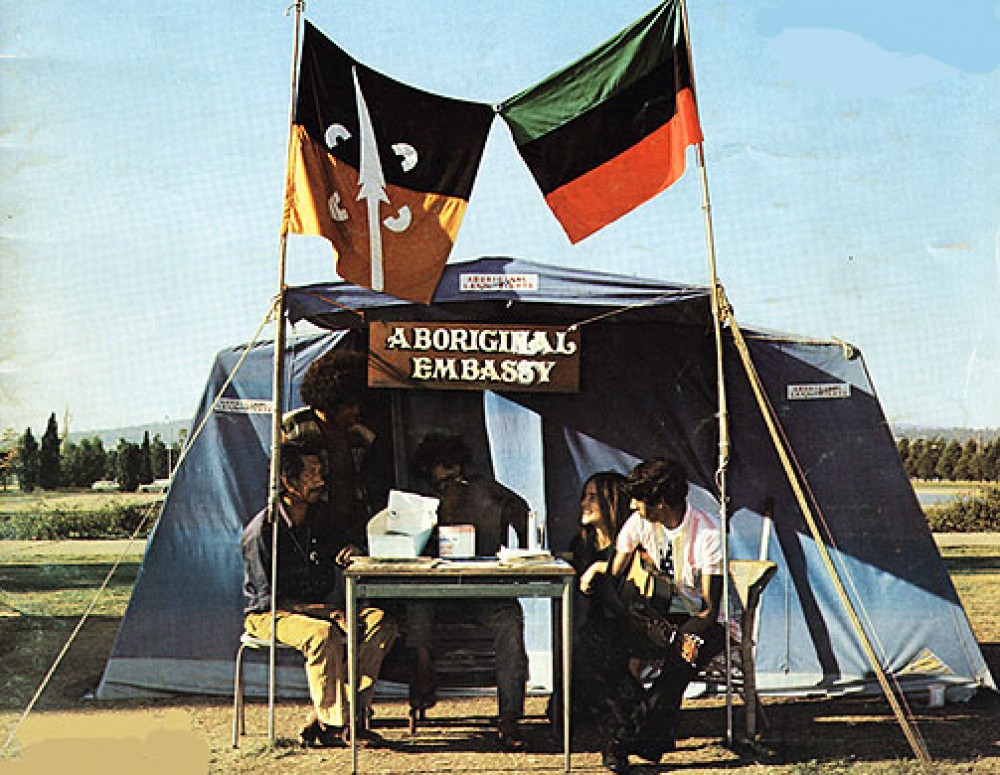

Precursors of Harold Thomas’s now official Aboriginal flag flying at the original Aboriginal Embassy in Canberra in 1972. Image courtesy www.kooriweb.org

Precursors of Harold Thomas’s now official Aboriginal flag flying at the original Aboriginal Embassy in Canberra in 1972. Image courtesy www.kooriweb.org

BM: One of the most prominent modern indigenous symbols is the flag designed by Harold Thomas in 1971. The black half of the flag represents the Aboriginal people of Australia, the red half represents the red earth, the red ochre used in ceremonies and spiritual relation to the land, and the central yellow disk represents the sun, the giver of life and protector.

BB: Joe Geia, wrote a beautiful song, Yil Lull, inspired by the flag: “I sing for the black and the people of this land / I sing for the red and the blood that was shed / Now I'm singing for the gold of a new year growing old.”

JG: The flag is now recognised as an official flag by the Australian Government, but its role as a symbol of resistance and unity for Aboriginal people began when it was adopted as the official flag of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in Canberra (an enduring makeshift protest camp on the lawns of the Old Parliament House) in 1972. Today, it flies in front of government buildings, schools and sports grounds alongside the Australian flag, itself a tired symbol of empire with the Union Jack stuck in the top right corner.

AB: But following Cathy Freeman’s somehow controversial flying of the Aboriginal flag at the 1994 Commonwealth Games, didn’t the Sydney 2000 Olympic committee try and ban the flying of flags other than the Australian National Flag in the stadium?

The Boxing Kangaroo, a flag regarded as Australia’s national sporting emblem, hanging at the Olympic Athletes' Village Vancouver, British Columbia 2010. Photo by Philip M. Tong.

The Boxing Kangaroo, a flag regarded as Australia’s national sporting emblem, hanging at the Olympic Athletes' Village Vancouver, British Columbia 2010. Photo by Philip M. Tong.

BM: Yea, which would have meant bloody true-blue Aussies couldn’t even fly the boxing kangaroo mate! Racism’s collateral damage…

Uluru at sunset. Photo by Jane Bligh.

Uluru at sunset. Photo by Jane Bligh.

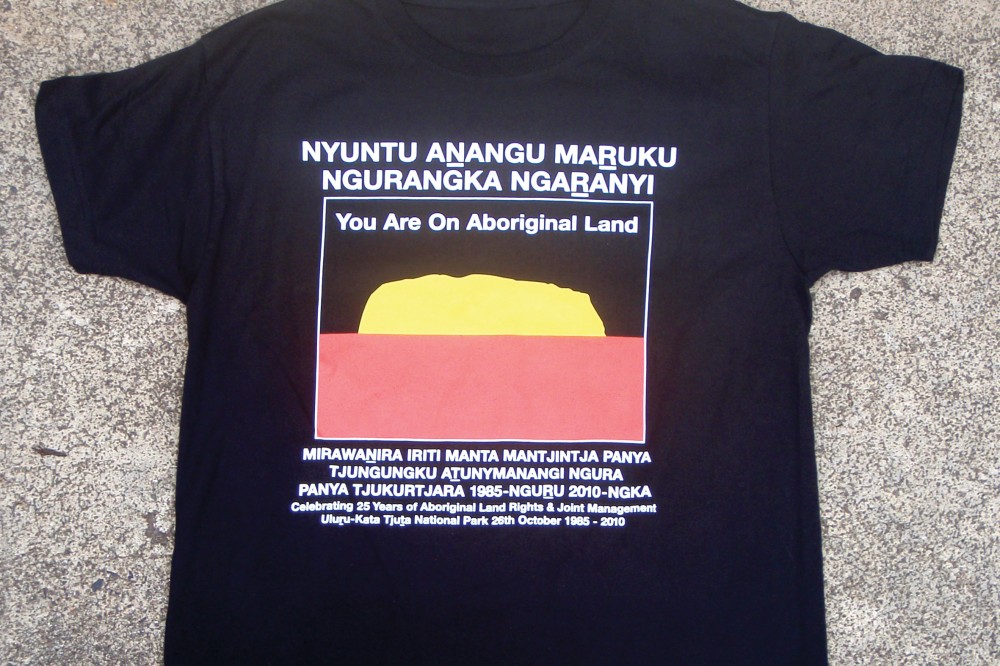

BB: I’ve just been on a road trip to the majestic Uluru and I thought a lot about the flag. The massive sandstone rock stands incredible against the desert backdrop — a landscape that was formed, according to the Anangu people, in an ancient process of creation and destruction. The rock formation shares an awe-inspiring symbiotic visual relationship with all that surrounds it, from its ever-changing alliance with the sun, to the red earth that circles its base and beyond. There are endless echoes of the Aboriginal flag in the landscape.

T-shirt commemorating the partial handback of Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park to traditional owners in 1985. The Uluru graphic reinterprets the Aboriginal flag. Photo by Jane Bligh.

T-shirt commemorating the partial handback of Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park to traditional owners in 1985. The Uluru graphic reinterprets the Aboriginal flag. Photo by Jane Bligh.

BM: Did you climb the rock?

BB: Well, they say 100,000 people a year ignore the signs from traditional owners asking tourists not to climb. It’s still an irresistible rite-of-passage for many non-Indigenous Australians, and international travelers alike. But it wasn’t a big effort for us to respect the Anangu people’s wishes and stay on the ground. The land rights for Uluru were partially passed over to the traditional owners 25 years ago, yet the Government continually refuses prohibition of the climb. This isn’t just disengaged cultural insensitivity, but also a deeper sort of stubborn cultural dominance and arrogance.

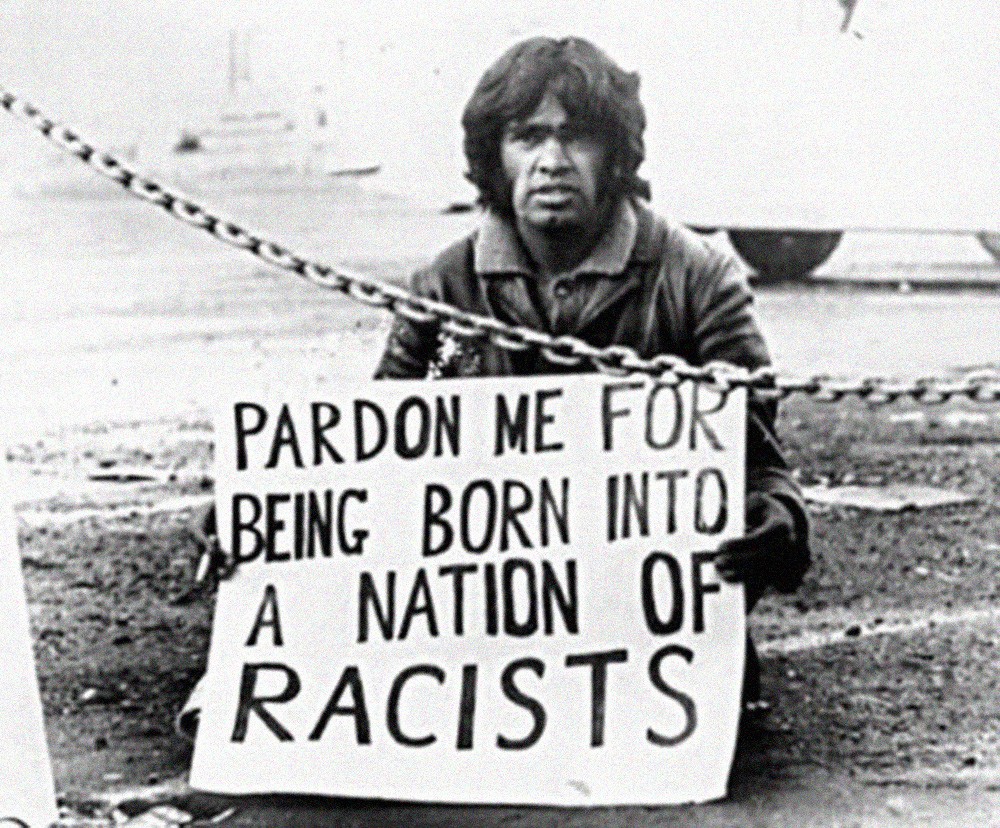

BM: But at the same time though, racism has always been challenged.

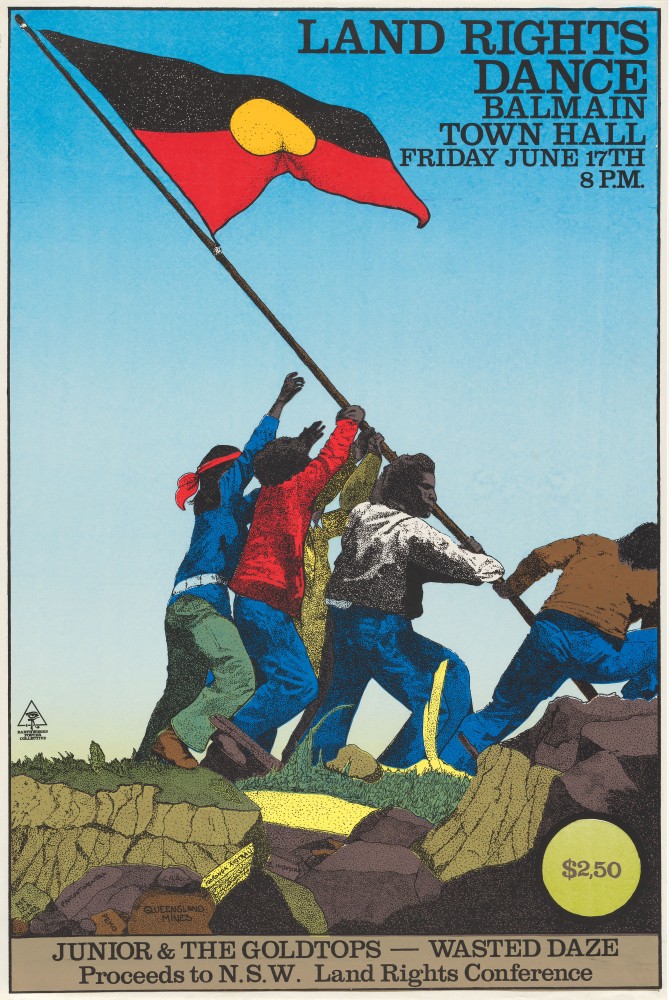

Chips Mackinolty, Land rights dance, screen printed poster 1977. Courtesy National Gallery of Australia.

Chips Mackinolty, Land rights dance, screen printed poster 1977. Courtesy National Gallery of Australia.

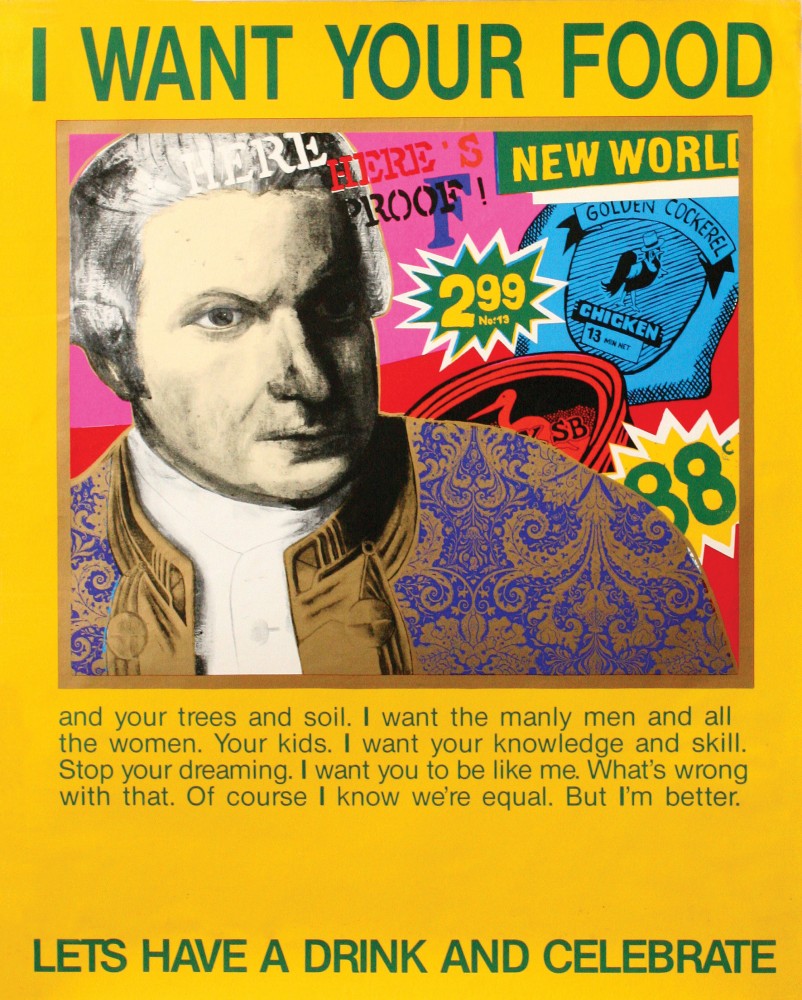

Stephen Nothling (Black Banana), I want your food, screen printed poster 1988. Courtesy the artist. 1988 was the year of Australia’s Bicentennial celebrations.

Stephen Nothling (Black Banana), I want your food, screen printed poster 1988. Courtesy the artist. 1988 was the year of Australia’s Bicentennial celebrations.

JG: And by designers too. The 70’s and 80’s in Australia saw the rise of the street poster as a medium for the grass roots mass-communication of political comment and social action. Along with indigenous practitioners, many non-indigenous artists and poster collectives made screen-printed images in support of Aboriginal land rights, health and education initiatives, and issues around cultural awareness. Workshops like Redback Graphix, Garage Graphics and Earthworks Poster Collective, and print makers such as Michael Callaghan, Chips Mackinolty and Marie McMahon made significant contributions to campaigns for indigenous rights with graphic expressions of solidarity and reconciliation; all really important inspiration for Inkahoots.

Activist Gary Foley with a placard protesting the South African Springboks rugby tour of Australia in 1971 during apartheid. Image courtesy www.kooriweb.org

Activist Gary Foley with a placard protesting the South African Springboks rugby tour of Australia in 1971 during apartheid. Image courtesy www.kooriweb.org

Painting over an official sign in Brisbane. The words ‘Musgrave Park’ are replaced with ‘Aboriginal Land’. Image courtesy of Bob Weatherall.

Painting over an official sign in Brisbane. The words ‘Musgrave Park’ are replaced with ‘Aboriginal Land’. Image courtesy of Bob Weatherall.

BM: Some of the most potent visual resistance to colonialism is far from the considered aesthetics of designers or artists. Handmade signs by activists and community members are drawn and painted to be carried into conflict not just with political opponents but also with the sanctioned authority of compliant commercial and state propaganda.

Commonwealth Government’s intervention sign in the Northern Territory. Courtesy Amnesty International Australia, 2011.

Commonwealth Government’s intervention sign in the Northern Territory. Courtesy Amnesty International Australia, 2011.

Sign for the Urapuntja Health Clinic located on fly dreaming country (Amengernternenh). Courtesy Amnesty International Australia, 2011.

Sign for the Urapuntja Health Clinic located on fly dreaming country (Amengernternenh). Courtesy Amnesty International Australia, 2011.

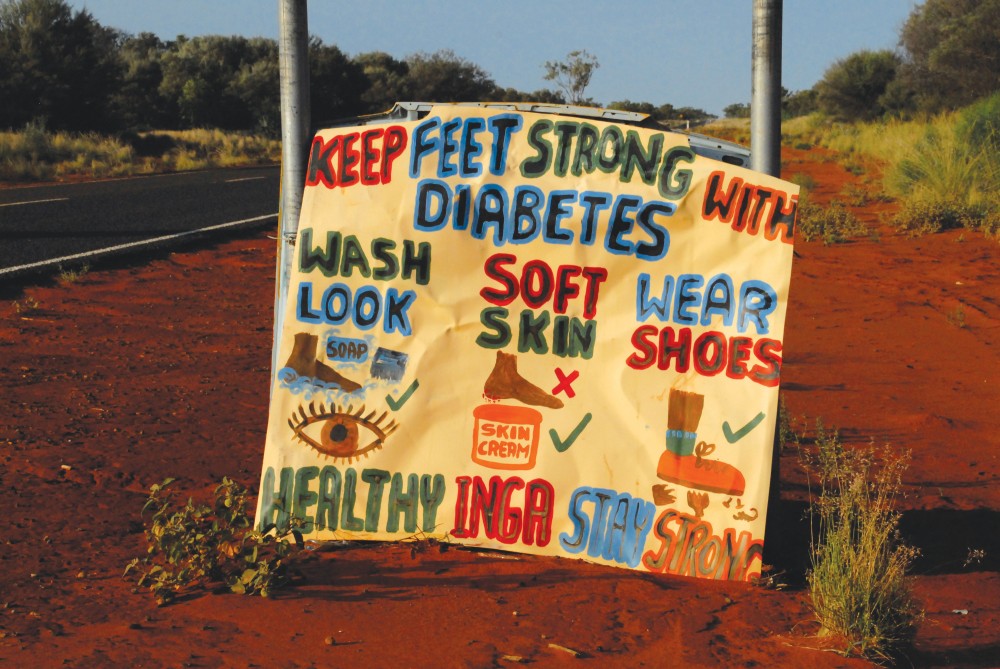

Sign on the Sandover Highway promoting health education. Courtesy Amnesty International Australia, 2011.

Sign on the Sandover Highway promoting health education. Courtesy Amnesty International Australia, 2011.

JG: If you’re travelling in central Australia you might come across obscene official signs that are a legacy of the Howard Government’s Northern Territory Intervention warning that the community is a ‘prescribed area’ and that liquor and pornography are forbidden. Would you want to drive past this bullshit provocation on the way home every day? Countering this ugliness are the beautiful hand painted car bonnets flagging community services and information. So on the one hand we have the toxic waste of racist government policy, policies that have failed to adequately consult and involve communities and therefore generally fail aboriginal people, and on the other, communication artefacts determined by the community’s own values and priorities. It really is a duel between human and dehumanising communication.

Australia Come Walkabout (stills), Commercial directed by Baz Luhrmann for Tourism Australia, 2008.

Australia Come Walkabout (stills), Commercial directed by Baz Luhrmann for Tourism Australia, 2008.

AB: Then there’s the ways in which the images generated by the tourism industry, corporate advertising, and state propaganda to project an idealised national identity often appear to ‘embrace’ Aboriginal culture. I’m thinking now of Baz Luhrmann’s emotionally manipulative ‘Come Walkabout’ advert where a young white couple has their crumbling urban relationship saved by an indigenous spirit who magics them down-under for metaphysical rejuvenation. Such representations of indigenous culture are still fixed in relation to the ingrained discourse of colonial entitlement and dominance.

JG: What is being colonised is Country of course, but also imagination. The possibility of real alternatives, the potential of other ways of being in the world are occupied by a totalising ideology that profits from racism. Our hopes and dreams for a better future are colonised. So any project of decolonisation is actually everybody’s business because everybody, black and white, will benefit in very real ways from this freedom.

BM: The last word goes to artist Gordon Bennett from his ‘Manifest toe’: “If I were to choose a single word to describe my art practice it would be the word question. If I were to choose a single word to describe my underlying drive it would be freedom. This should not be regarded as an heroic proclamation. Freedom is a practice. It is a way of thinking in other ways to those we have become accustomed to. To be free is to be able to question the way power is exercised, disputing claims to domination. Such questioning involves our ‘ethos’, our ways of being, or becoming who we are. To be free we must be able to question the ways our own history defines us.”